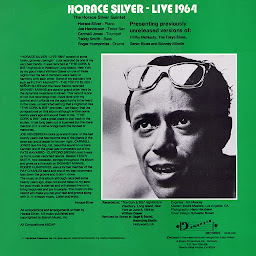

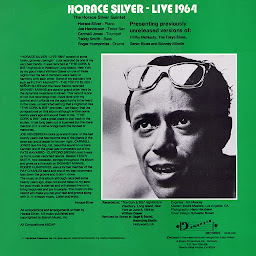

Horace Silver - Live 1964

Horace Silver's 1965 album Song For My Father showcased a new band with Carmell Jones on trumpet, Joe Henderson on tenor saxophone, Teddy Smith on bass, Roger Humphries on drums, and Silver on piano. Except for "Calcutta Cutie", the majority of the album (not counting bonus tracks) was recorded in October 1964. That track was done in October 1963 and Silver may have wanted his band to work a little together before recording again. Live 1964, released in 1984 on Emerald Records, a subsidiary of Silver's Silveto label, features the band in live performance from June 6, 1964 at "The Cork & Bib" nightclub in Westbury, Long Island, New York.

This is a good document of a good band working together to become a very great band. There are flashes of brilliance, but it's not quite there yet. The piano is quiet on side one performing "Filthy McNasty" and "Skinney Minnie" but otherwise the performances are good. Side two with "The Tokyo Blues" and "Señor Blues" are the standout tracks. It's particularly interesting not hearing Silver's longtime frontline Blue Mitchell on trumpet and Junior Cook on tenor, not play these tracks. The music is still Hard Bop, but the avant-garde is never far away particularly with Joe Henderson on board. Henderson and Jones also have more understated sounds than the old frontline who were more extroverted sounding. "Señor Blues", for example, doesn't have that urgency in the louder sections of the studio recording. The quieter section is exquisite with Henderson and Jones sounding mysterious and teasing even.

Joe Henderson (1937-2001) is the person most responsible for the new sounds of the Horace Silver Quintet. By this time, he had already recorded a few solo albums for Blue Note. On Song For My Father it feels like all of his signature sounds and ideas were all set in place. Aside from a few moments, where he seems to be doing a Junior Cook impersonation just because he replaced him, Henderson's sounds like his own man. On Live 1964, Henderson sounds like himself, but his sound explorations sound more experimental. Those wailing repeated gestures in the upper register of his horn are missing. The repeated gestures are there, but he seems to stick mostly to the lower register of his horn on this date.

Silver's improvisations are as much explorations as he tries on new ideas which lead to others. "Señor Blues" begins with a long Silver piano solo and on this minor blues, he takes his time. It's not quite modal (that minor sixth makes a reappearance), but he spins out endless ideas on this tune, quoting a traditional song along the way. The rhythm section builds his solo, but he prefers to play without too much movement from his rhythm section. Bassist Teddy Smith plays a simplified version of the bass line but he rarely moves away from the part. Drummer Roger Humphries keeps things grooving.

Silver's improvisations are as much explorations as he tries on new ideas which lead to others. "Señor Blues" begins with a long Silver piano solo and on this minor blues, he takes his time. It's not quite modal (that minor sixth makes a reappearance), but he spins out endless ideas on this tune, quoting a traditional song along the way. The rhythm section builds his solo, but he prefers to play without too much movement from his rhythm section. Bassist Teddy Smith plays a simplified version of the bass line but he rarely moves away from the part. Drummer Roger Humphries keeps things grooving.

|

| L-R: Teddy Smith, Joe Henderson, Roger Humphries |

Originally from Kansas City, Carmell Jones (1936-1996) is a solid toned trumpet player, but he seemed to have shown up to the Hard Bop party a little late. Being based in Los Angeles didn't help either as the Hard Bop scene was centered in New York. But by the time of his tenure with Silver in 1964, the jazz scene had been steadily disintegrating with clubs closing and opportunities to play slowly fading. The sound explorations of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane were gripping everyone and while it made for some great music, it did not help the struggling jazz scene stay afloat. Jones would eventually move to Europe in 1965. Though he moved back to Kansas City in 1980, he unfortunately fade from the scene.

He has the solid, dark, brassy sound of Clifford Brown, but his improvisational style is understated. He doesn't grab you by the throat like Lee Morgan or Freddie Hubbard, instead, I think he's more of a groove player, falling in and playing with the rhythm section. He should be more of a household name, but he was overshadowed.

Bassist Teddy Smith (1932-1979) is originally from Washington, D.C. and like Jones, just showed up to the party too late. He had already worked with Betty Carter, Clifford Jordan, Kenny Dorham, and Jackie McLean by the time of this recording. But after a stint with Sonny Rollins in 1965-1966 he seemed to have vanished out of sight. The only other jazz musician I really know from the capitol is, lol, Duke Ellington, but actually a contemporary of Smith was the bassist Butch Warren (1939-2013) who was active also in the early 1960s working as part of the house rhythm section for choice Blue Note records. Smith is a solid if pedestrian accompanist. He takes a long solo on "Skinney Minnie" and it's impressive. It is an extremely refreshing take on a bebop solo by a bass player in a field dominated by Paul Chambers, Ray Brown, Sam Jones, and others, It's a note-y solo (he doesn't rest much), but he's right in the chord changes. He demonstrates good technique, extended range, and a wide base of ideas in his solo.

Drummer Roger Humphries (b.1944) is the lone surviving member of the quintet (as of July 2020) and was only twenty at the time of recording. Prior to working with Silver, he worked with fellow Pittsburgians Stanley Turrentine on tenor and Shirley Scott on organ. He would go on to have a long career, playing and recording with Ray Charles and others remaining active throughout at least the 2000s. He is a strong figure in the Pittsburgh jazz scene.

Silver had had a steady band for almost five years with Blue Mitchell, Junior Cook, Gene Taylor on bass, and either Louis Hayes or Roy Brooks on drums. But Silver was already well known in jazz circles. He pioneered Hard Bop with its use of copious amounts of gospel and rhythm and blues gestures in his improvisations and, significantly, his compositions. It seemed to be a rather natural sequence of events as most jazz musicians had started out playing rhythm and blues. Hard Bop was now more well-rounded with a dose of blues in the middle of those fast, double-time bebop lines and gestures.

"Filthy McNasty" was a hit single for Silver in 1962 (it was released as a single anyway!) and it is a blues shuffle. The twelve-bar harmonic form is reduced to three chords, but the sophistication lies in the theme : the first eight bars feature a repeated swing riff, while the last four bars has breaks and the melody played with a straight staccato eighth-note feel. It's an effective change of feels that seems to be a nod to the current "shuffle-boogie" fad of the early 1960's that also mixed swing and straight eighths at the same time. The tune is rounded out with with a short interlude featuring syncopated rhythm section hits that serves to launch the first soloist. All of these details (there's also a shout chorus before the last theme) are Silver trademarks and part of his genius.

Carmell Jones sticks to the blues and groove, but Joe Henderson is looking for ways to incorporate all of those Coltrane sounds he'd been practicing. As he does on the rest of the tracks, he sticks to the lower register of this horn and also plays the blues, but his sound is more mellower and not as raucous. The Lester Young single-note trick makes an appearance in his solo.

"Skinney Minnie" does not appear on any studio record by Silver. It's a dark, minor key piece with an unusual half-step movement from the I minor chord to the bII minor chord. Jones is excellent throughout this recording and here his blues playing is different than the last tune with a whole new repertoire of ideas. Henderson seems constrained on this tune and seems to be frustrated. On this album, all of the tunes follow the same structure: starting at a low volume point before building to a climax. It's predictable but it's exciting when executed well. Henderson seems to be annoyed on this track to have to follow the same pattern again, or at least his solo, which does build nicely, does not not seem to be going the way he would like to. He even misses a few notes here and on the melody to "Filthy McNasty".

"Tokyo Blues" which opens side two is the best track on the album. Maybe it's the bII major seven chord going to the I minor chord, but everybody sounds relieved on this track. Jones' solo is strong and even mixes in a little "A Night in Tunisia". Henderson, though, is brilliant here. Everything has fallen into place for him and his solo just grows and grows. Like Silver he goes from idea to idea, but unlike Silver he'll stick with the same idea over different chords. It's one of his trademarks and it's a nice way to not feel locked in with the chord changes. He grooves nicely with the rhythm section, but continues to improvise even after they bring the volume and intensity down, perhaps on cue or thinking he was done.

Silver solos on the other tracks but he's not miked properly and it's impossible to hear him. He's more audible on side two and he sounds like his usual self: alternating blues, bebop, and motivic ideas. He sounds inspired by Henderson's playing with chromatic ideas. Silver also alternates vertical and horizontal approaches to improvisation---after the bII major 7 chord, he plays the natural minor sixth on the I minor chord. But then he'll stick to an idea and transpose it through the scale. Now and then, he'll lighten it up with some down-home blues playing. It's a very satisfying mix.

Silver's improvisations are as much explorations as he tries on new ideas which lead to others. "Señor Blues" begins with a long Silver piano solo and on this minor blues, he takes his time. It's not quite modal (that minor sixth makes a reappearance), but he spins out endless ideas on this tune, quoting a traditional song along the way. The rhythm section builds his solo, but he prefers to play without too much movement from his rhythm section. Bassist Teddy Smith plays a simplified version of the bass line but he rarely moves away from the part. Drummer Roger Humphries keeps things grooving.

Silver's improvisations are as much explorations as he tries on new ideas which lead to others. "Señor Blues" begins with a long Silver piano solo and on this minor blues, he takes his time. It's not quite modal (that minor sixth makes a reappearance), but he spins out endless ideas on this tune, quoting a traditional song along the way. The rhythm section builds his solo, but he prefers to play without too much movement from his rhythm section. Bassist Teddy Smith plays a simplified version of the bass line but he rarely moves away from the part. Drummer Roger Humphries keeps things grooving.Unfortunately, this unit on Live 1964, would not last long and only Humphries would remain for the next band. Silver would not have a steady band (at least on record) until the mid-1970s. But there exists some great live footage of the band at the Antibes Jazz Festival in France in 1964 performing "Tokyo Blues" and "Pretty Eyes". As far as I know, this music has not been released on cd or streaming, so for now the videos will have to do.

Comments

Post a Comment