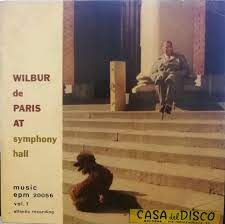

Wilbur de Paris at Symphony Hall

The subtitle of this record is "Wilbur de Paris and his New New Orleans Jazz" and that's an apt title. In the liner notes, written by de Paris, he distances his music from the then trendy "dixieland" jazz; Some of our fans believe I am getting too far a-field, or that this is not "dixieland", and I agree, it is not and isn't intended to be, but a New New Orleans jazz. Tempus Fugit." The album was recorded in Boston on October 26, 1956 and features de Paris on slide and valve trombones, his brother Sidney de Paris on cornet, Omer Simeon on clarinet, Sonny White on piano, Lee Blair on banjo, Benny Moten on bass, and Wilbert Kirk on drums and harmonica. Stylistically it is definitely a far ranging album than other New Orleans jazz artists and expands the possibilities within the genre. Despite the strong New Orleans flavor, the music is also highly informed by the musical aesthetics of the Swing era. It's an interesting blend two and reflects the wide and varied experiences of its musicians, especially its frontline.

Drummer Wilbert Kirk was the newest member of de Paris' band in 1956, but he was from the same generation as everyone else. Originally from New Orleans, Kirk was raised in St. Louis and played on the Riverboat Jazz Bands that went down the Mississippi River. Along the way, he had stints with Don Redman, Claude Hopkins, and Noble Sissle. He also happens to double on harmonica allowing to lead some novelty bands in the 1940s.

During moments of collective improvisation, it is almost always the cornet playing the melody or improvising with the clarinet responding or commenting. The trombone is more discreet, but now then makes its presence known. Also, although there are individual solos, there's a loose attitude towards the sacred solo space. It really feels like, if one person is improvising, the other is welcome to add lines as they wish. The community feeling is very strong and dominates over the individual.

"Wrought Iron Rag" features a unison melody from the front line. It's a very long form and the piano solo here is closer to ragtime-style though the syncopations are not as pronounced. The last two originals are features for Blair and White.

de Paris' choice of covers is interesting and covers a range of music: "Juba Dance" was written by the late 19th century African American classical composer, Nathaniel Dett. Juba is the style of body percussion (slapping various parts of one's body) that emerged in the mid-19th century and "Juba Dance" is part of a suite of African American folk songs. de Paris' jazz version features clarinet on the melody in the upper register. Simeon is the main improviser here during ensemble parts.

I assumed Wilbur de Paris (1900-1973) was born in New Orleans, but he was born in Indiana and got his start in music in his father's circus band playing vaudeville. He moved around quite a bit in his younger days, playing with Louis Armstrong and A.J. Piron in New Orleans in 1922, as a leader in Philadelphia, then with bandleaders LeRoy Smith, Dave Nelson Noble Sissle, and Edgar Hayes in New York. In the late 1930s, he worked with Teddy Hill, the Mills Blue Rhythm Band, and then Louis Armstrong's big band for three years from 1937 to 1940. He had a stint with Duke Ellington (late 1945 through early 1947) and made recordings with Sidney Bechet at the end of the 1940s. From 1951 until 1962 he played regularly at Ryan's in New York. The music on At Symphony Hall, and the band, is a result of this long-running gig.

Cornetist Sidney de Paris (1905-1967) also a had long career as a sideman working in the 1920s with Charlie Johnson and McKinney's Cotton Pickers. He spent 1932-1936 with Don Redman before freelancing with a range of early jazz and swing artists like Willie Bryant, Mezz Mezzrow, Zutty Singleton, Sidney Bechet, Art Hodges, Claude Hopkins, before playing with his brother from the mid-1940s. At ease when playing collective improvisation with clarinet and trombone, his cornet solos are played with a mute that seem to come aesthetically from Duke Ellington and the plunger mute, a sweet tone that's closer in spirit to, say, Cootie Williams, than Louis Armstrong, and a penchant for blues devices. A well-rounded "early jazz", de Paris did not always fit in with everybody.

Clarinetist Omer Simeon (1902-1959) also has career that begun in the early jazz era. Originally from New Orleans, Simeon's family moved to Chicago when he was twelve as part of the great migration of African Americans moving northward or away from the Deep South. In Chicago, he took lessons with master New Orleans clarinetist Lorenzo Tio, Jr. who developed a method of playing the clarinet that facilitated jazz playing (Barney Bigard also studied with Two). Simeon got his start in his brother's band before joining Charlie Elgar's Creole Orchestra in the mid-1920s. He played and recorded as part of Jelly Roll Morton's 1926 Red Hot Peppers recording sessions before playing and recording with King Oliver, Luis Russell, and Jabbo Smith. By this time, he had added alto and tenor saxophone to his repertoire and this led to his tenure with Earl Hines from 1931-1937. After stints with Horace Henderson and Coleman Hawkins, he joined Jimmie Lunceford's band in 1942 staying until the band was led by Ed Wilcox and Joe Thomas in 1950 (see my post here on that band). He had been playing with de Paris in New York since then and would until he passed away in 1959.

Pianist Sonny White (1917-1971) also brought a wide range of skills. Originally from Panama, he got his start playing with Jesse Stone in 1936-1937. Until the early 1940's, he worked in the dance bands of Willie Bryant and Teddy Hill, recorded with Sidney Bechet, and was Billie Holiday's accompanist from 1939-1940, playing piano on the original recording of "Strange Fruit". He continued this range of work playing in the big bands of Artie Shaw and Benny Carter, backing vocalists Big Joe Turner and Lena Horne, and was versatile enough to play with Dexter Gordon in 1946. White had a long steady gig with an obscure trumpeter named Harvey Davis before joining de Paris's band.

Left-handed banjoist and guitarist Lee Blair (1903-1966) was from Savannah, Georgia. Like Simeon, he played with Jelly Roll Morton in the late 1920s before playing in the big bands of Luis Russell and Louis Armstrong from 1935-1940. He was freelancing through the 1940s before joining de Paris at Ryan's.

New York bassist Benny Moten (1916-1977) had played with trumpeters "Hot Lips" Page and Red Allen from 1942-1949. Afterwards he gigged with violinists Eddie South and Stuff Smith and tenor saxophonist Arnett Cobb in 1953-1954 before joining de Paris.

|

| Wilbur Kirk |

The harmonica definitely adds an interesting flavor to New Orleans music, but it fits right in as there are lot of interesting sounds on this great record. For example, instead of maintaining a two-feel, the rhythm section plays mostly in 4/4 time, which is not unusual in itself, with Kirk on the cymbal and Moten walking, but the banjo is playing quarters. It's a nice sound and banjoist Blair's knowledge of guitar probably softens the banjo's sound.

It's a band of seasoned professionals and based on their experiences, it seems like there's been some overlap going back thirty years. They know each other's playing well and I noticed that they all improvise in a very similar fashion: succinct improvisations that showcase their sound. The phrases are wonderfully played, the music is very festive, and the blues is always there. Even when they don't play a blues, the songs sometimes sound like a blues! It's the feel and the attitude that the musicians bring. I would say that it is the authentic blues sound and attitude of the musicians that distinguishes New Orleans Jazz (their brand or otherwise) from Dixieland bands.

|

| Alternative cover |

The primary soloists on this album Sidney de Paris on cornet and Omer Simeon on clarinet. Although this album is released under Wilbur's name, he only takes a few solos and is content playing as a member of the ensemble. That some trombonists place greater value on ensemble work is an underrated and under appreciated aspect of their musicianship. So many great trombone soloists in jazz history are tremendous section and/or lead players from Carl Fontana, Bill Watrous, Frank Rosolino to Bill Reichenbach, Jim Pugh, and Andy Martin. Few trombonists are soloists only and sometimes jazz history overlooks these other types of musicians who have valuable skills required for big bands and other work.

Wilbur de Paris did contribute five originals. After introducing the band, "Majorca" opens the album and alternates between a latin jazz and swing feels for each chorus. With the rhumba rhythm and harmonica melody, it's an auspicious start but then goes into a deep swing feel for Simeon's clarinet solo. Before the cornet solo, there is a short interlude featuring the bass and piano's left-hand playing a figure in unison. The timbral textures are quite unique and could be classified as cool jazz meets New Orleans! The song also has a couple of unusual chromatic changes (for a New Orleans-style song anyway) and Simeon makes those changes, providing a change from his blues-drenched solo.

The first four bars of "Toll Gate Blues" has a wonderful melody harmonized for the three horns. Decorated with some diminished passing chords, the next eight bars features the frontline improvising. It's a slow blues and the bass line carries the pulse. White on piano takes a wonderful solo, plays a sparse stride. It's not super busy, but those left-hand tenor notes ring out nicely. He has an interesting piano-style that isn't quite stride, but not quite bebop either. Like pianists of the earlier generations, he focuses on textures and doesn't care to show off any technique. He reminds me a little of Jess Stacy in this way, For Simeon's solo, the music breaks down to a duet with clarinet and banjo, with the tremolo chords creating a nice texture. Simeon is more refined than, say Johnny Dodds, but he gets into the gut blues sound here in a big way.

|

| CD two-fer with "Searchin' and Swingin'" |

"Banjoker" features the banjo playing the melody upfront with either single notes, tremolos, or chords. For solos, banjo trades eights with alternating cornet, clarinet, and trombone. It's surprisingly confusing sometimes to figure out the structure, as sometimes the horns will collectively improvise for a few bars at the beginning of a chorus before dropping out. A drum break leads to a double time feel before Blair finishes it out with a short, chordal cadenza.

"Piano Blues" is taken at a slow pace (12/8) and White begins with several choruses upfront. It's not quite a twelve-bar blues and there are some additional unusual harmonic changes. He's not a harmonic player and sticks loyally to the chords, preferring to vary his phrases and textures. He's a very unusual pianist whose solos are pointillist in nature---it's not details, but the big picture. In pianists like White and Jess Stacy, modern jazz is not far away.

|

| 1957 7" EP |

"Cielito Lindo" is a popular Mexican song dating back to the 19th century. This too is played swing and features trombone on the melody, de Paris' glorious sound up front. "Sister Kate" by A.J. Piron feature Kirk on harmonica. He plays bluesy chromatic harp in the beginning, then after a chorus of cornet and clarinet trading, Kirk comes back to solo with the diatonic harmonica. It's a very dense and heavy sound, but the band is swinging hard with everyone in the frontline joining and commenting.

"Farewell blues" is the lone standard and was originally written and recorded by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings back in 1922. This version features two sections: a swinging collective improvisation alternating with a one chord latin vamp over which there are individual solos from the front line. It's kind of like "Sing Sing Sing" except with banjo playing chords. Quite the modern take on an old track.

The last thing I'd like to point out is the intent of the music---it's pretty much solely focused on the musicians. The presentation of the music is more artistic than entertainment. Music of the pre-bop era was for dancing and there's too much change going on here for dancers. The spirit of earlier styles of jazz are alive but played with a strong sense of artistry. I guess it was recorded at a classical venue, so perhaps there was an intent to make their music more "serious". Whatever the intent, the results are interesting and show that these musicians from the earliest stages of jazz's history, were still making interesting music that challenged their and the public's notions of the New Orleans jazz. Most musicians of earlier eras don't change and prefer to play the music of the past. Wilbur de Paris and his New New Orleans Jazz band did that but they updated their sound and meaning of their music---without losing the heart of it.

Comments

Post a Comment